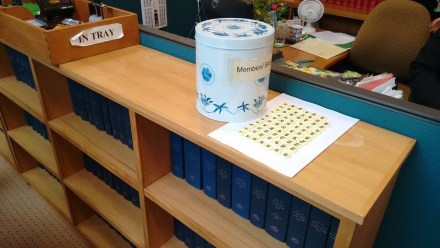

This is a picture of a tin. A very important tin.

It looks like Nana’s biscuit tin, but is actually the tin from which ‘members’ bills’ are drawn ‘from the ballot’ every second Wednesday of the month in Parliament. If we were to see inside the tin on such a Wednesday we would see roughly 80 of the numbered plastic tiles in the photo above, each one identifying one MP’s private bill waiting to see the light of day. Many of them won’t.

Private members’ bills provide for some of our most important social reforms.Louisa Wall submitted her private member’s bill on same-sex marriage in May 2012; it was drawn in August 2012, enacted into law by April 2013. Legal and social history was made.

In October last year another tile went in the tin; David Seymour’s End of Life Choice Bill. And there it waits. It is the latest in a growing line of such tiles; last year Maryan Street’s End of Life Choice Bill was withdrawn after languishing for 18 months, and a lack of enthusiasm shown by Labour leader Andrew Little in 2013, an election year. Back in 2003 NZ First MP Peter Brown’s “Death with Dignity” bill was only narrowly defeated in a conscience vote 60-58 at its first reading. In 1995 Michael Laws also had a go; only to be defeated by a much wider margin (61-29 against).

Euthanasia is not a new issue, but it seems to me that medically-assisted dying, as one kind of euthanasia, has received a lot of positive media comment and profile recently.

- Maryan Street’s submission of a petiton to Parliament seeking law change to allow assisted dying received good coverage here, here and here. In fact, the Health Select Committee has launched a Parliamentary inquiry as a result of the petition, for which submissions closed on 31 January.

- Lawyer Lecretia Seales sought to have the Courts interpret the Crimes Act 1961 in such a way that her own doctor would not face prosecution for helping her to die. The Courts declined the opportunity just before her death, leaving any such reform to Parliament.

- Trade unionist and former head of the CTU Helen Kelly, in coming to terms with her own terminal illness, has also sought the right to assisted dying.

- Cases involving people seeking to end their own lives at a time of their choosing is being reported perhaps more favourably in the media as a prime example, Peter and Patricia Shaw who killed themselves in October last year).

- There has been some considerable debate within mainstream media outlets about euthanasia. I know this because Stuff has a tab under its ‘National’ news page called ‘Euthanasia’, so it must be true.

In my view there is considerable work has been done that is preparing the ground for David Seymour’s Bill to be ushered into law should it be drawn. Of course politics being what it is, the Bill may not succeed anyway. Nevertheless the time is ripe now for Māori and Pacific peoples to be heard in what is developing into a nation-wide debate. Except I’m not hearing them. Well, that’s not entirely true. There are a few opinion pieces here and there, but nothing like the furious debate at the time of the Royal Commission on Genetic Modification (200 submissions were received by Royal Commission from Māori, for example), and the attention (rightly) given to Māori suicide prevention generally.

What might Māori and Pacific practices around death and dying have to reveal about assisted dying? What might tikanga reveal? While religious creed might uphold the sanctity of life, how might such creeds influence or cohere with tikanga Māori perceptions of the sanctity of life? In the scraps of material I have seen Māori and Pacific peoples are divided; there is no one view about euthanasia, including assisted dying. There are few signals coming from Māori politicians; the Māori Party is non-committal although ‘open to a debate’ while Marama Fox is unconvinced assisted-dying legislation is needed. Metiri Tūrei has voiced support for the current Parliamentary Inquiry, but little more.

To be fair, there may have been a plethora of Māori and Pacific voices included in the submissions to the inquiry that closed three weeks ago. I hope so, but I feel somewhat doubtful, given the lack of chatter about the issue detectable on social media at least. We’ll see once the inquiry progresses. The late Amster Reedy was cited by the Nathanial Centre in its own submission to the current Parliamentary inquiry:

“We bring people into this world, we care for them right from the time they are conceived, born, reared, in health, sickness and in death. The rituals still exist for every part of our lives – we just need to have faith in our ancestors. Euthanasia is foreign to Māori and has no place in our society.”

Penehe Patelehio (Tokelauan, Samoan, Cook Island) was cited in the same submission:

“When someone is ill or dying, the idea of assisted-suicide or euthanasia is entirely foreign to us. There is no word in our language for this concept and consequently it does not enter into our thinking. The opportunity to care for and look after someone who is ill or dying/suffering is seen as a blessing even though it may present significant financial and other challenges. At such times the extended family and community networks come to the fore – it is common for immediate and extended family and community members to visit, provide food, and massage and converse with the person who is ill.”

For me personally the debate is not really about the value of life vs the value of personal autonomy to choose to die. Both things are good and neither are absolute. I recognise that the value of life, or the right to life will not always win over other considerations (the ability in law to defend oneself to the death from attack is an example where the life of the attacker is not to be preserved at all costs). In my mind that debate is actually a little sterile, but important for those who want to contribute to it. I want to ask instead: how vulnerable might elderly or sick Māori and Pacific peoples be within a regime that allows assisted dying?

One of the oft-cited great risks of any assisted dying regime is that elderly people facing the end of their lives due to illness will seek to end their lives prematurely so as not to be a ‘burden’ on their families. Others might seek assisted dying, not so much at their own behest, but at the behest of others family members. In a society where 1 in 10 older persons (and proportionally more Māori) are reported to experience some kind of abuse especially connected to vulnerability and coercion, such risks must not be ignored.

To be honest, the idea of assisted dying frightens me. I am not really frightened of the idea of humanely ending the life of someone in terrible and terminal pain, although I cannot extricate my Christianity from my position that life is worth preserving. I can understand, though, why there appears to be so much public support for such a choice to be allowed. Many of those who voice such an opinion have watched their own friends and/or family die. Who am I to gainsay their experience?

Indeed my fear stems also stems from personal experience: from our mother dying from lung cancer last year. We were fortunate enough to have been with her over those last weeks and months of her life as her physical presence declined and her mind became incapable of lucid decisionmaking. I wrote a post on this blog about our experience at the time. Her death did not frighten me; it was the realisation of the power we had over her shrinking life. We had absolute control over her money. I, and my brothers made the decisions about where she lived and where she died. Her possessions became ours in practicality well before her will made that legally possible. I had real power over my mother’s life. What frightened me was the prospect that I should have had any power whatsoever over her death. My mother would have, without hesitation, signed any end-of-life directive (had that been available to her) to absolve medical staff of responsibility, or naming me or one of my brothers the decision-maker regarding termination in the event of her mental incapacity.

To be fair to David Seymour his Bill is careful to ensure some safeguards that will minimise at some of the risk that vulnerable people might face; and makes no provision for the kinds of advance directives that would have given us the power to end Mum’s life after she lost the capacity to decide for herself. But the Bill only goes so far; the initial medical professional who receives a request for assisted dying under clause 8(2)(h) must:

do his or her best to ensure that the person expresses his or her wish free from pressure from any other person.

Forgive me, if these few words seem oddly subjective and lacking in effectiveness. The medical practitioner is not charged with ‘ensuring’ the absence of coercion (and perhaps this is simply not possible), just doing his or her ‘best’ to ensure such. Whatever ‘his or her best’ might mean. If that clause is all that stands between a coercive and abusive family and an elderly person choosing to die as a result of that coercion, I am not yet reassured. Should the Bill be drawn, surely this clause will need one heck of a lot of work.

We all know the law and lived reality are two very different creatures. Make no mistake; today there are elderly people, at least some of them Māori or Pacific; who will likely be subject to some degree of coercion, if assisted dying becomes legal in a country already distinguished by high rates of Māori suicide, and growing rates of suicide among the elderly. Surely it is time for more Māori and Pasific speakers to step onto the marae ātea for this issue. In readiness for the time a certain tile comes out of Nana’s tin.

[Please note this post is available at E-Tangata in a slightly edited form.]